One day, Flute Boy thought to himself, “I should ask Wéilán my question. He will know this.” So, off he went to find his uncle. Wéilán was his father’s eldest brother; Chángdí grudgingly respected his uncle. His uncle Wéilán could be short to the point of rudeness with his answers to questions that he felt were simple or beneath him. On the other hand, if you asked a question that uncle thought was a good question, the answers could be very long-winded and boring. However, Chángdí knew that his uncle was well-respected by other people. Others called him “Lǎo Dàoshi”, meaning “Old Daoist.” Besides, Wéilán always had the answer to Chángdí’s questions.

Chángdí played his flute quietly as he walked along to the village. He knew that uncle Wéilán had gone to the village for tea, as he did most days. In the tea shop, Wéilán would sit for hours talking with friends and strangers alike, which was why Chángdí called his uncle Wéilán which literally meant “fence post” – uncle could talk to a fence post and hold a conversation.

When Chángdí got to the tea shop, he went inside. His uncle was sitting alone talking with no one, which was unusual. However, it meant that Chángdí could ask his question without waiting for his uncle to finish a conversation. As he approached, uncle Wéilán, without turning to face Chángdí, said, “What have you come to ask me?” Chángdí was surprised that uncle even knew he was there. As if reading his mind, Wéilán said to Chángdí, “I heard you playing your flute as you approached the tea shop. No one else in the village plays the flute quite the way you do. Chángdí took this as a compliment and swelled a bit with pride. Then his uncle said, “Your flute is of such poor quality that it makes a rather distinctive sound.” Uncle Wéilán continued, “But it makes no difference, I am glad you came. Now I have someone to talk with. What would you like to talk about?”

Chángdí set his flute aside before asking his question. He said, “Uncle, I have a question and I think you will know the answer.

“Quite likely,” replied his uncle.

Frowning a bit, Chángdí asked his question, “Uncle, when I meditate, nothing seems to happen. Even if I sit for a long time.”

Uncle Wéilán asked, “What do you expect to happen?” But before Chángdí could answer, uncle continued, “I have watched you. You do not meditate for such a long time. I imagine that it seems to be a long time to a young boy like you, but in reality it is only a few minutes.” Uncle did not stop there, “Chángdí, we have talked about this before, successful meditation takes diligent practice. After all, one cannot expect an oak tree to grow to great height without nurturing the seedling.” Uncle Wéilán kept going, “Do you not remember the three harmonies? It is the most basic practice.”

Finally, uncle paused long enough to let Chángdí respond. “Yes, I practice the three harmonies, but nothing seems to happen. I feel no different.”

Uncle asked, “Do you focus on the Dan Tien?”

Chángdí then asked somewhat hesitantly, “What is the Dan Tien?”

“There it is. That is your problem!” said Wéilán. Continuing on, uncle explained that the Dan Tien is an energetic spot located just below the navel and a few inches inside the body. He then said, “One must start out by focusing on the Dan Tien, also known as the elixir field. Focusing on this spot takes time for results to appear. Often, it takes 100 hours of meditation. If you meditate for twenty minutes per day, that will take about 10 months. An hour per day will only take about three months.”

Chángdí said, “An hour? Each day?”

“Well, some lucky people feel the changes sooner, but many do not,” stated Wéilán. “Practicing daily is more important than the length of practice. Hence, daily practice of short duration is more beneficial than sporadic practice of long duration. But, most beneficial is daily practice of long duration – the longer the better.”

Chángdí pondered this while Wéilán sipped his tea. Finally, Chángdí asked, “How does one know that their meditation is beneficial?”

“Ah, an excellent question,” replied Wéilán. “One knows that their meditative practice is working when they feel a warmth in the Dan Tien. Some people will feel a sensation of a turning of the Dan Tien; as if it is turning like a wheel. When these sensations have grown quite strong and are not increasing, one can begin to practice the Microcosmic Orbit.”

“What is the Microcosmic Orbit?” asked Chángdí.

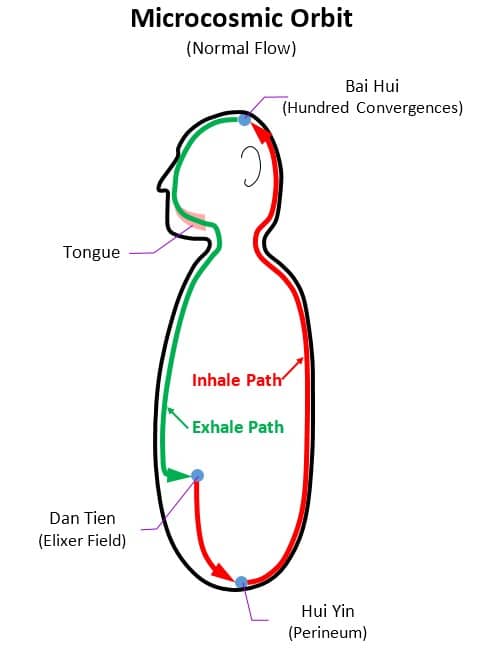

Wéilán said, “One can feel their chi flowing through their body. Starting at the Dan Tien with an inhale, the chi moves downward to the Hui Yin point,

then up the back, through the neck and up to the Bai Hui point. While exhaling, the chi moves down the front of the body and back to the Dan Tien. One trick is to touch the tip of the tongue to the roof of the mouth just behind the front teeth. This is necessary to complete the circuit.”

“Where are the Hui Yin and Bai Hui points located?” asked Chángdí.

”The Hui Yin point is located at the bottom of the torso, just between the anus and the genitalia. The Bai Hui point is at the crown of the head – not the center of the head, but on-line with the ears at the highest point of the head,” explained Wéilán.

“One more question, said Chángdí, “How does one know that their practice of the Microcosmic Orbit is beneficial? And, what are its benefits?” asked Chángdí.

“That is two questions, not one,” corrected Wéilán, “so, I get to provide three answers. One can tell that they are benefiting from practice of the Microcosmic Orbit by noting the strength of the flow, and by noting that the Dan Tien warms. The benefits of the microcosmic orbit is to refine and purify your jing into chi and your chi into shen. This provides health, longevity, and if one is lucky, immortality. It also provides martial abilities to the practitioner. Finally, as with most everything else in Tai Chi Chuan, its practice must be balanced. This means that one should practice with the flow going in both directions. Practice first in one direction several times, then in the other direction the same number of times. You will know the reverse flow is beneficial when the chi begins to stick to and warm the back. This is magical, Chángdí; it is as if the quality of your flute improved each time you played it!”